The aim of this study was to have a better understanding of unpaid care work in Albania - what is the state support regarding the unpaid care work of women, what are the social services that the state offers to women in order to cope with their household work and responsibilities? What is the link between women’s unpaid care work and their economic engagement? What is the understanding of women and men of their rights vis-à-vis state support regarding family and unpaid care work?

It is important to note that in this report we define “social services” not only as services targeted for groups in need, but also as all services for the improvement of living standards such as care for children, care for the elderly, education and health care services, and provision of the population with the basic needs such as electricity, sanitation, water, etc.

For conducting the focus group discussions, ASC selected 10 municipalities, Kukës, Shkodër, Lezhë, Rrëshen, Tiranë[17], Elbasan, Librazhd, Pogradec, Fier and Vlorë. These regions were selected in order to represent all areas of the country, and also different characteristics such as different levels of poverty, labour market, migration, opportunities, potentials, etc. Also, ASC conducted focus group discussions in two periphery areas: Vau i Dejës in Shkodër and Paskuqan in Tirana. These areas were selected based on their specificities but also as two ex-rural areas now considered urban (Vau i Dejës now is a municipality and Paskuqan has been often at the centre of discussions on whether to become a municipality.) Vau i Dejës is an area very near Shkodër, with a high number of emigrants (abroad and in other areas of the country), high rate of poverty, but what is more important - with a very high rate of female unemployment. Paskuqan is the peripheral area of Tirana, currently inhabited almost exclusively by migrants coming from the North of the country after the 1990s. [18]This area is now under the process of legalization but still there is a very high level of informality.

Profile of participants

The division of our participants by sex was 46.27% male and 53.73% female. The average age of men participating in the focus groups is 43.9 years old and the average age of women is 40.8 years old. The majority of the participants’ households are composed of four members, which is nearly the average number of household members for urban areas. Only 6.33% of them live in households with 7 members and 1.81% in households with 8 and 9 members. As this study is based on urban areas there are not many extended families, because as data shows[19], in the urban areas, the average number of family members is 3.9. An analysis of the diaries shows that 17.33% of the participants reported that they receive economic aid (Ndihme ekonomike NE), which is the governmental program of assistance to address poverty in Albania. This means that they are in the category of the poor, according to the official definition of poverty in the country.[20]

Based on the discussions in focus groups and the time use diaries, it can be seen that most of women’s time during the day is spent on maintaining the household and care for children.

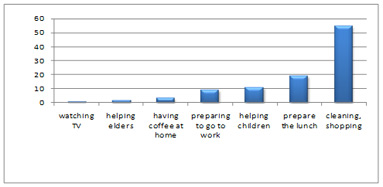

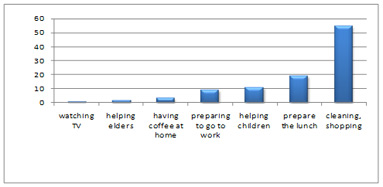

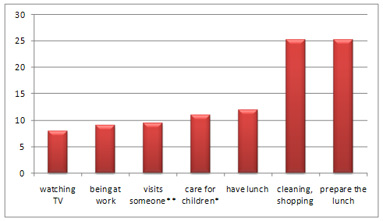

Graph 2: Main activities in the morning 7.00-11.00 (% of women)[21]

Source: Own analysis of time use diaries

As we see from the graph, more than half of women participants have as main activity in the morning cleaning, shopping and dealing with other housework. Preparing lunch is another activity and also the care for children. In terms of time during this interval, in the time span of 240 minutes in the morning, it results that 134 minutes are spent for cleaning and shopping.

The majority of men diaries show that during this interval they go to work. The rest of them, those that are unemployed, spend most of the time in the morning by going out in search of a job, or going out with friends in bars.

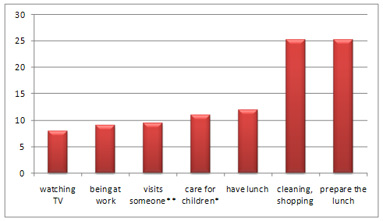

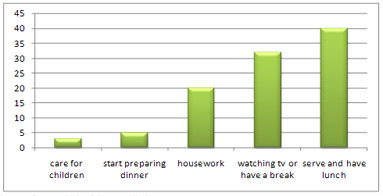

Graph 3: Main activities for women at noon 11:00-15:00, (% of women)

Source: Own analysis of time use diaries

*taking kids from school, preparing lunch for them, helping them in other things, etc.

** in most cases, parents or parents in law

As we see from the Graph 3, during the noon period, the activities of housework and cooking remain the main activities for the majority of women participants. Another activity is the care for parents and parents in law and care for children. For around 12% of women, “care for children” is the main activity. In this interval of time, around 8% of women report as their main activity “watching soap operas.”

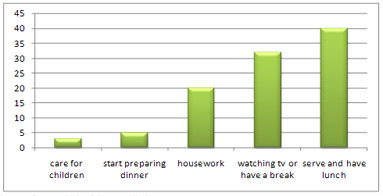

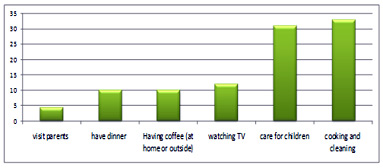

Graph 4: Main activities of women in the afternoon 15.00-19.00 (% of women)

Source: Own analysis of time use diaries

The afternoon period (Graph 4) is the one where women have some free time spent in watching TV while the lunch is the main activity. It must be said that the expression used by women for this activity was “serve lunch to the husband,” because they wait for their husbands to come back from work around 5 o’clock p.m. and that is why they have lunch so late.

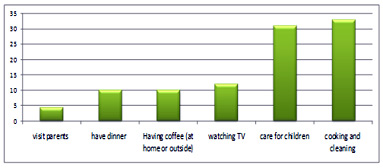

Graph 5: Main activities of women in the evening 19:00- 23:00 (% of women)

Source: Own analysis of time use diaries

Care for children means not only taking care of small children but also help children with homework and other school engagements.

From Graph 5, we see that housework becomes the main activity, because around 33% of women report as their main activity cooking and cleaning in order to pre-prepare work for the next day. Care for children is the main activity for around 32% of women.

There are gender differences in the amount of leisure time for women and men. The research reveals that women have very little leisure time, compared to men, due to their household responsibilities. This is the case both for paid working women and for the unemployed/not economically active. As they say, women spend very little time for themselves, or for their entertainment. This is seen also in the fact that women smile sadly at this question by saying that they do not have time and money to spend for themselves. This was mostly the case in Paskuqan, Vau i Dejës and Rrëshen and this could be linked to the higher poverty rates of these areas. In the case of these regions, focus groups reveal that this is related to the patriarchal mentality that assumes that women have to care for everyone else in the household and only at the end they may care somehow for themselves. In the other cases, it was more a question of lack of time due to household obligations and lack of incomes. This is related to the issue of economic dependency of women as a very sharp problem, which we will come back to later in the report.

As it results from discussions in focus groups and from the diary processing, the main activities women engage in during the day (05.00-23.00), are household engagement, (housework, cooking) and caring for children and other family members; that is not the case for men who report mostly to be at work, searching for a job, meeting with friends in bars, or playing some sports.

There are very few women that report reading a book, or going out to the cinema or theatres (this is also because of the lack of offers of cultural activities for both women and men). But, while men can go out have a coffee with friends, or engage in some sportive activities, this is not the case for women. Thus, the nature of leisure activities for men and women is different – while for the first this takes place mostly outside the household, the latter are contained within the household. Regarding the weekend, women in focus groups said that this was a time for more housework. They almost do not go out of their home, except for doing shopping for the household or pay visits to relatives and friends.

Therefore, the burden of a job and of caring for the house and family members represents a considerable obstacle to women’s participation in the social and political life. The lack of social and civic participation significantly limits their abilities to understand and be aware of the types of socio-economic programmes, services and opportunities available to them in their communities and beyond. The situation is quite different for men who spend considerably more time outside the household. When it comes to engagement in public life, women do not participate in debates or meetings organized by the local government. Sometime they say they have no information about such debates, but in other cases (and this is very important) they say that do not have any reason to participate because they do not have any hope for change, they are very pessimistic and even if they participate this is useless. The lack of trust in meetings or debates was expressed both by women and men. The meetings or activities organized by non-governmental organizations are in general the only possibilities for participation. The situation was much more problematic in areas where there is an absence of such organizations.

However, we noticed that very few of the women participating in the FGs emphasize this non-participation in the social and political life as a problem. For economically non-active and unemployed women, finding a job was mostly related to payment. They say that if they do not find a well-paid job, they would prefer to stay at home. As our research reveals, however, this often means isolation from activities that are not contained to the household and even lower opportunities to engage in public life.

Discussions in focus groups indicate that in most cases, men have the role of decision making in the family. This was seen mostly after focus group participants were asked who kept the family budget. Most of them (both women and men) said men kept the budget of the household. This was accompanied by women’s comments that it should not be men as they do not know concrete household needs, or spent money on things that were not useful to the whole family, etc. Men, on the other hand, said that they were the head of households, and some of them were saying that “we are the ones that bring more income home.” When decision making relates to the spending of money, in the vast majority of cases, the final decision is taken by men of the family, who also reserve the right to decide on the number of children, their education, migration or immigration of the family or one of its members, as well as on the marriage of children. Women have more of an informing and advising role about the need to purchase particular food items, or they advise on selling home-made products.

This issue is very much related to women’s access to income and economic dependency. As pointed above, it may be seen also in their comments that women, compared to men, spend very much less for themselves, only in cases “when really needed.”

“Women's participation in decision making inside the family is also influenced by poor access to information and knowledge. Living an isolated social life negatively affects access to information. Empowerment of poor women and women in the rural areas in decision making inside the family increases with an increased education level and increased access to information, as well as with increased income. A range of non-governmental organizations work towards this aim, and they have extended their outreach to the regions where there is a concentration of unemployed and thus poor women, offering them information, advice, and also supporting professional development”[22].

What we find from the research is that the lack of information and limited access to social services is one of the issues (but not the sole reason) that leads to women being “locked” in their unpaid care work responsibilities. In the section below, we make an analysis of the main social services that could support women regarding their unpaid care work.

Care for children, the elderly, and other family members

One of the main responsibilities in unpaid care work is that for children. Children care is one of the main issues to be analyzed when talking about women’s engagements in general. This may sound a repetition but in Albania, as in most countries in the world, women are considered the only persons responsible for child care. During the communism period, due to policies encouraging women’s full employment and education, there were public day care centres and kindergartens for children.

After the 1990s, with the major changes that took place in the Albanian society, the existing system of child care institutions experienced serious and negative changes. In this case, it should be emphasized that the process of decrease in these institutions and the closing of jobs for women may be considered very closely related. If we look at figures in years (given below), we notice that there is a major drop in the number of kindergartens both as institutions and number of children enrolled in kindergartens. The drop came as a result of the overall turmoil that took place in Albanian institutions, which was accompanied by the closure of numerous schools, kindergartens, enterprises, etc. Another reason that goes in parallel with it is the closing down of numerous jobs after 1990, which mostly affected women. Women’s withdrawal from the labour market toward the home led to a decrease in the number of children attending day care centres and kindergartens as it was preferable to keep children at home as opposed to sending them to day care centres or kindergartens with poor conditions and away from places of residence (which, in the unsafe situation of the time, may be considered a very significant factor, particularly for the rural areas[23]).

Based on focus group discussions, one of the main points raised by women participants was precisely the lack, both quantitative and qualitative, of day care centres and kindergartens. They said they took care of their own children because they had no confidence in public institutions, day care centres or kindergartens, or because it was very difficult to enroll children in the really good ones. For example, during focus group discussions in Tirana, one of the participating women, who was expecting a child, said she had not yet decided whether she would return to her job after the maternity leave because there was no one to take care of her child: she had no relative in retirement, the quality of public day care centres was poor, and “good quality ones are scarce and hard to enter”; at the same time, her income did not allow for a private day care centre or a babysitter. Thus, the opening of private day care centres and kindergartens does not appear to have solved the issue for new mothers because often they cannot afford the cost.

At present, preschool institutions (kindergartens) that admit children between 3 and 6 years old are under the Ministry of Education and Science as they are considered institutions for children’s first education. Day care centres, which may be considered institutions taking care of children 0-3 years old, are under the local government. There is an increasing number of private day care centres but the quality that they offer costs more and is more difficult to be afforded.

The decrease in the number of institutions for the care and education of children 0-6 years of age has not seen any considerable increase and comparison to the period before 1990 remains impressive. Compared to 1990, in 2003 there were 60% less kindergartens in urban areas, and 49% less in rural areas. According to the LSMS 2002, the principal reason why children were not sent to kindergartens is their unavailability or the long distances required to reach them. Regarding the child care system covering the group age 0-3 years there is almost no official information. According to unofficial data only 10% of children 0-3 years have access to kindergarten.[24]

Should we refer to data from the LSMS, we find that poverty is another factor affecting the rate of children enrolled in day care centres and kindergartens. The National Enrollment Rate (NER), for the non-poor is 38.4%, for the poor 18.2%, and the extremely poor 10.0%.[25] Much fewer children from poor families attend kindergartens compared to those from less poor families. According to MICS 2005, significant differences remain between children living in the richest households - 59.2 percent attend pre-school - and children from the poorest households - only 25.7 percent attend pre-school education institutions.

As a result, we may also assume that women in the poorer families are more disadvantaged as they cannot benefit from different services or facilities which have a cost. Another factor that has led to the demise of preschool institutions is the lack of adequate funds. The pre-school budget makes up only 5% of the total budget of the Ministry of Education and Science.[26]

Besides care for little children, which results to be one of the causes for non-participation in the labour market, we may also add something about the issue of care for children attending school. According to analysis of discussions at focus group meetings, most women say they take care of children’s progress in school. They are the ones accompanying children to school, participating in teacher-parent meetings and following the progress of children and their results in school. This of course, impacts women’s performance in the labour market – both informal and formal. The number of men saying they take care of children is very minor. In general, also based on the analysis of diaries, men return home very late after leaving the home very early in the morning.

Care for the elderly

From the focus groups discussion it came out that women care not only for their children and husbands but also for the elderly in their households. As mentioned above, the number of extended family participants in the research is quite low because we focus only on urban areas. Thus the activity of caring for the elderly is not among the most time-consuming of women in urban areas – but there is reason to think this would be different for those women in the rural areas where extended families more commonly live within one household. As we saw in the graphs above, among the activities in the morning “caring for the elderly” was the main activity for 2% of the women. Also, during the time-span 11.00-15.00 around 11% of women go visit and care for parents and parents in law.

According to the two strategies (Strategy of Social Services and Social protection Sector Strategy) one of the groups in need are the elderly. Thus, according to the definition of social services used by these two strategies, the elderly are one of the priority beneficiaries of the state social services. However, social services are addressed toward single elderly people, in centres or at home and not those who live in families. Thus, no link is made with the unpaid care work of women in these strategies. As the strategies are addressing only single elderly people, it results that for the others the responsibility goes to the family which as in many other cases replaces the security nets that should be provided by the state.[27] But, within the household, the responsibility and the burden of caring for the other members on top of other household duties goes almost exclusively to women that are the most suffering from poor state support. Regarding care for the elderly, the provision of institutions is not the only way of care, even though this is still needed. Another way of care would be the primary health service at home.[28]

There is still a high number of old people living with their children (married or single). According to the Census data, we have a large number of married young couples living with the parents of one of them. Living with husband’s parents has been a universal practice before the establishment of the communist regime in Albania.[29] During the communist regime, as the nuclear household was proclaimed the nucleus of the society, the state tried to provide young married couples with housing. But after the crisis of the end of 1970, it was very difficult for young couples to get an apartment, and there was a return of co-residence. After the 1990s, we still have large numbers of co-residence, but in this case it is because of mutual support, considering that the situation is very difficult for young people that cannot afford to buy or rent an apartment, but also for the elderly who cannot live alone with the very low old age pensions and the lack of many facilities.[30]

Social protection

The social insurances system includes the old age pension, unemployment benefit, maternity leave,[31] disability benefits. As mentioned above, the majority of women participating in the focus groups are not involved in paid protected jobs. Thus, they are not included in the social insurance system. They know only that they can pay social and health insurances voluntary but they find it very expensive and unaffordable. This fact is reported also by men. The majority of men are paying social and health insurances, but they find it quite impossible to pay the voluntary insurances for their wives. The fact of being insured or not in the health care system was reported as useless because in any case “you have to pay something”[32], and women are the most discriminated as being dependent economically from their husbands.

There is no specific family benefit, or program on child welfare, but there is some supplementary compensation to the amount of pensions and of unemployment benefits for children /family members under their dependency, as well as compensation related to the increase of the price of bread and electricity, all financed out of the state budget.

With regard to access to health services, most women participating in the focus groups, being withdrawn from the labour market, were not included in the social and health insurance schemes. For that reason, they said they had to pay cash for any medical check-up or treatment. Nevertheless, even those participating women who were employed and insured admitted that, in general, they had to pay for health services in cash. [33] It should be emphasized here that women take very little care of themselves. They stated that they only spend time and money for themselves only when it is quite necessary. In fact, even when they are ill, they go to health care centres only after taking care of other family “obligations.”

The gender policy analysis of the Ministry of Health[34] shows that if we were to make a connection between the reduced number of beds in hospitals and the increase of the use of these beds, there appears to be a contradiction. The explanation may lie in the impossibility of keeping patients in the hospital for a long time (which is sometimes necessary). Thus, patients have to leave the hospitals in order to make room for others who need hospital health services. Another element that we should keep in mind from state institutions is the fact that the stay of ill persons in hospitals has dropped. This leads directly to an increase of home care for the ill. Usually, care for the ill is a role mostly played by women, thus increasing their burden in the family; this is accompanied by a decrease in their efficiency at work outside the home (if they are employed). What needs to be emphasized in this part is that social services may not be considered any more only as services for groups in need, but rather should be expanded more broadly. Care centres for children or the elderly should not only target ill or orphan children, but everyone, thus serving as powerful support in terms of house engagements and the multiple burdens that women have to bear.

Referring to the same document, one notices a decrease in the number of visits to mother and child care centres. This is considered a very important problem that has long-term repercussions as it directly affects the health of mothers and children, their good upbringing and feeding. At this point, we should keep in mind the fact that such services assume priority particularly in special areas where, as a result of migratory movements, the number of young uneducated girls has grown and they suffer from lack of education on the importance of self health care, lack of information on reproductive health care, etc. In such conditions, this service is fundamental, both for protecting mothers’ health and for raising a healthy generation.

According to discussions in focus groups and after interviews with nurses of consultancy rooms that we contacted in Librazhd, Tirana and Paskuqan, it appears that there is a marked drop in the number of visits by pregnant women before birth. There is a decrease of the prenatal care and women go to make a check up only in the last month of pregnancy.

Albanian legislation offers special support and health care services to mothers and children. “All pregnant women benefit from free periodic medical pregnancy checks, before and after delivery, especially compulsory pre- and postpartum examinations, determined by the Minister of Health Act”[35]. Despite their wording, implementation of these provisions as well as the quality of health service is inadequate.[36] During discussions with women in the focus groups and interviews with the nurses, it was said that according to a recent rule, pregnant women who do not have a health record book do not benefit from such free service. Due to many women’s informal or absent labour market participation and consequent lack of health insurance, they cannot benefit from the free services even with regard to prenatal care, which limits their rights and their well-being.

There is a decrease not only regarding prenatal care but also post-natal care for women and for children, in the case of employed women. In Paskuqan, the nurse told us that there are a lot of cases where young mothers are obliged to begin working and caring for the household very few days after delivering. They are obliged mostly by their mothers in law that say that “delivering is nothing, we have had 8 children and then back to work” so “it is not normal to stay in bed, or have check ups after birth”. This points to other forms of traditional gender norms that are still present and affect women’s position and well-being.

According to interviews with nurses of health care centers for mothers and children, many young mothers are forced to return to work quickly, without taking advantage of the entire maternity leave. This often happens because they risk losing their jobs and because, in some cases, payment during maternity leave is much lower than their salary[37].

There is no official data related to cases of discrimination because of pregnancy or motherhood in the public or private sector. However it is thought and confirmed by some of our focus group participants that in the private sector, women are subject to discrimination on the above-mentioned grounds. Typically, a woman does not get employed if she is pregnant or if she has small children. There are no cases of reporting to court and this might be because of the lack of knowledge of the relevant legislation that guarantees labour rights for this category of women, or maybe because of lack of trust of women that they can effectively protect/earn their rights, therefore they do not make any denunciation.[38][39]

From the time use diaries, it is obvious that water supply is one of the activities of women during the day, while this is not the case for men. Thus, alongside cooking, cleaning, caring for children and other family members, they have to provide the household with water, which is not being supplied by the responsible institutions, from common sources in the neighbourhood.

Water supply has always been problematic in Albania but the situation has deteriorated even further recently due not only to an increase of demand for water but also as a direct consequence of low investments in the water supply infrastructure dating back to the communist period and recent draughts. Only 53,1% of the Albanian population has access to in-house running water and 16% percent has outside access. The percentage of the population that has no access to running water is still very high and stands at the level of 30%. This lack of investments is accompanied by bad management of existing resources which has created a problematic situation where wide areas of the country suffer lengthy shortages of water. Only 47% of the population has continuous running water during the day, whereas the rest of the population enjoys only 6 hours of daily water supply. [40]

The power sector in Albania is facing a crisis. While demand is on the rise, resources to deal with it have not changed. Even the existing resources have not been administered well during this period. This situation has turned the issue of power supply into one of the sharpest and most acute problems that the Albanian society is facing nowadays. 85,7% of households experience some sort of electricity shortage, whereas 71,5% of them have daily power interruptions. The average daily power supply has been 6-8 hours. The same picture comes out of the analysis of heating data. Central heating has been and continues to be almost non-existent in Albania. The heating situation has not improved even after the ‘90s. Therefore, 99,9% of Albanians do not have access to any sort of central heating. The majority of the population, around 58,1%, use wood stoves for heating, with gas and electricity heating following with respectively 25,4% and 13,5%.[41] In this paragraph, data refer to LSMS 2002; however, the electricity supply situation remains just as problematic today and, in some cases, has worsened. We can then assume that the situation for women in rural areas must be worse regarding heating and cooking, because women have to gather the wood by themselves, which seems not to be the case in urban areas where there are private businesses for this. Many documentaries about the situation of women in rural areas often show women carrying on their backs the wood for heating, cooking, etc.

The supply of electricity, water, and sanitation is a very important aspect with regard to services facilitating women’s household unpaid care work. In the course of discussions in focus groups with women and men, one of the questions dealt with the situation of house appliances, which are helpful for women’s housework. All participants said they had all necessary appliances at home, including refrigerators, washing machines, often vacuum cleaners, stoves, etc. However, at the same time, the lack of water and electricity, makes their use impossible during most of the time because (with the exception of Tirana that experiences shorter water and electricity outages), outages of electricity and water are very considerable.

According to focus group participants, the possession of household appliances was no longer as important – they were almost not used, particularly appliances most useful to women, such as washing machines or vacuum cleaners. Besides, lack of water and electricity supply forces women to spend a great deal of time trying to ensure water from outside the household. This leads not only to great physical strain, but even to psychological duress, as they admitted themselves. The lack of water and electricity also has an impact on the hours they spend to take care of children or housework. The lack of water and electricity is a problem that affects everyone, but women are the ones suffering the most from such deficiencies because they are responsible for housework, for caring for children, the elderly, and other family members. Women (and children in some cases) spend a lot of time getting water from common sources in the neighbourhood. Not only is this time consuming but more importantly, this affects their physical and overall condition because they have to do heavy works for getting water, hand-washing, etc., and could experience less sleeping hours, more psychological pressure, etc.

The unemployment rate among women is higher than that of men. According to official statistics provided by INSTAT in 2006, the unemployment rate for women is 16.8 and for men is 11.8.[42] But, what is more important is that women are retiring from the labour market becoming economically inactive. Issues of women’s economic activity mostly regard the difficulties in entering the labour market. The difficulties are related to the fact that most jobs are more appropriate for men (such as the construction sector that is the most important one, as reported by the majority of participants). Another problem highlighted in the discussions is that in some cities, such as in Fier and Vlorë, there is age discrimination among women. Young, unmarried women are more preferred that the ones married, with children etc. The difficulties of women to enter the labour market were highlighted during all FG discussions. [43]

Another important factor is the high involvement of women in the informal non protected labour market. As mentioned above, there are 60% female workers in the informal labour market in the private non-agriculture sector. This means that among employed women in the private non-agriculture sector, 60% of them are involved in the non protected labour market, which is an entire group of women excluded from the entire social insurance system. When asked if they would prefer to have a paid job or stay at home and care for the household, the majority of women say they would prefer the paid job. But they added that they would prefer to have the paid job only in the formal sector, with paid insurances and regular contracts, and these jobs are mostly in the public sector[44].

Most of the women were discouraged from re-entering into the labour market. They stated that in the situation of having a low salary and having to pay a babysitter, it is better to stay at home and care by themselves for children and the house. Only few women participants, like in Pogradec, Vlorë and Fier said they would prefer a paid job for the sake of going out of the home, having a more active social life, becoming more active and having some independent income.

FG discussions revealed that women and men have some kind of information about courses and vocational training, but in most cases, these courses are useless as they often do not adapt to market demands, offered jobs are only in the informal market, etc.

Within the social insurance system is developed the maternity insurance branch with the following benefits: maternity benefits, maternity allowance, due to employment change, and birth grant. The maternity benefit is payable only to a woman with regard to pregnancy and childbirth, provided she has acquired 12 months of social insurance.

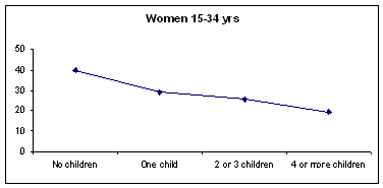

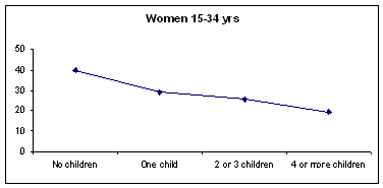

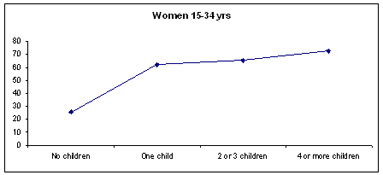

Census 2001 data shows that in urban areas, the greater the number of children, the lower the possibility for the mother to access the labour market.

Graph 6: Employment rates of the 15-34 years old women by the number of their living children: urban areas, 2001

Source: Census 2001

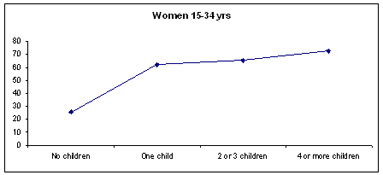

The unemployment rate among women 15-34 years old in urban areas is the exact opposite of the employment graph. Here again it is proved that women with 4 or more children are less likely to hold a job. It is important to say that it is not only a problem of accessing the labour market. The other important point is that mothers do not have facilities in order to match family responsibilities with the professional job. [45]

Graph 7: Unemployment rates of the 15-34 years old women by the number of their living children: urban areas, 2001

Source: Census 2001

If for women we say unemployed and out of the labour market (in the majority of cases) this is different for men. From the time use diaries, it seems that the majority of men were looking for a new job, which means that according to the official definitions, they are unemployed. This was not the case for women, because in none of the diaries was it stated that “I was looking for a job”. This was also the impression from the focus groups, that they say that they wanted to find a job, but in reality they do not really look for it. Even when there may be some opportunities, it is difficult that it fits to most of women, because of their engagements in the household. Due to their household work load, they say that they could afford a “part-time job, near their home, well paid, with all insurances paid.” There are many cases of girls and women themselves not accepting available jobs because of various reasons. During focus group discussions almost in all the cities except Paskuqan and Vau i Dejës, where women were not so interested in finding a paid job, women were saying that they would prefer work in the public administration (considered the only protected job), part time would be better so that they can care for housework, near their home, and with a good salary.

Research completed by the “Refleksione” Association during 2004 confirms these findings. Refleksione has assisted 895 women and girls in several districts of Albania such as Tirana, Shkodër and Pogradec to get employment and out of this total, some 170 women and girls have been employed. A large number of them have refused the job offered for different reasons such as low salary jobs, distance from the potential work place, lack of social services such as care for children or other family members, domestic violence in the household, prejudices and stereotypes at the work place, etc.[46] Besides, the wage offered does not justify the time spent and the difficult work conditions in some of the jobs. This brings to the development of the informal market or to unqualified and limited jobs, such as: secretaries, bar tenders, waitresses, etc. Furthermore, opportunities for employment in state institutions are almost absent.[47]

[1] Progress of Worlds Women 2005: Women, Work and Poverty” UNIFEM, p. 23

[2] The number of TU diaries is smaller than the total number of participants because for reasons of time, or not willing, some of them did not succeeded to fill out the diary.

[3] This is the number of focus groups with participants in the research. The total number of focus groups including local authorities and experts is 50 and the total number of people participating in these focus groups is around 400.

[4] Here it must be said that, in the case of women, it refers not only to “unemployed”. This category includes women unemployed but also women withdrawn from the labour market. The difficulty with the definitions is that for the majority of participants the term “unemployed” is used for all cases, even for the ones that are not seeking a job any more.

[5] According to official statistics in the pre-primary and tertiary education, the enrollment rate for girls is higher than that of boys. Meanwhile, in the primary and secondary education, the boys’ enrollment rate is higher. In the secondary education in 2004 the ratio of girls to boys is 0.94. Nevertheless, there is an important aspect to be highlighted, which is the difference between rural and urban areas. In primary education, there are no differences between rural and urban areas. Regarding the secondary education in 2004 the ratio of girls to boys in rural areas is 0.82 while in urban areas it is 1.(MDG 3 in NSSED progress report 2005).

[6] Danaj E., Festy P., Zhllima E., “Becoming an adult: challenges and potentials for youth in Albania”, Tirana, 2005

[7] Danaj E., Festy P., Zhllima E., “Becoming an adult: challenges and potentials for youth in Albania”, Tirana, 2005

[8] UNDP, Gender policy analysis in the MoLSA, Tirana, 2005

[9] Facts from the FG in Paskuqan

[10] Albanian Labor Market Assessment, World Bank, page 62, May 2006,

[11] Albanian Labor Market Assessment, World Bank, page 62, May 2006,

[12] ASC staff calculation by the data set of LSMS 2005

[13] This is referring mostly to non registered business

[14] In these cases, women are working in both places, being housewife and economically active at the same time.

[15] Albanian Labor Market Assessment, World Bank, page 65, May 2006,

[16] This section refers mostly to the World Bank report “Albania Labour Market Assessment” 2007 and LSMS 2005 data.

[17] In Tirana, two mini-municipalities, No. 5 and No. 6, were selected with each having different characteristics in order to have better representation.

[18] The informal buildings in Paskuqan are now under a broad process of legalization, but still the informality is the main problem for this area.

[19] INSTAT, Population in Albania 2001, Tirana, 2002

[20] According to the State Social Service (SSS), there is a set of criteria for being considered poor and thus receive NE, among which the most important are that the head of the household be unemployed and registered in the Labour Offices, not have properties for selling or renting, not have land (which excludes all employees in agriculture), be registered in the Civil Registry Offices etc., have no other household members active for work, etc. (SSS, Poverty Mapping, Tirana, 2002). There are a lot of criteria and the decision for entering in the NE scheme is based on a means-tested method. It must be said that currently there is needed a reform of the criteria of allocation of NE in order to distribute it according to a more precise poverty mapping, as LSMS could provide. (See Danaj E., Papps I. Policy Impact Analysis: Distribution of Economic Assistance Block Grants, MoLSA and MoF (Department of NSSED), 2005.

[21] The diary was divided into 2 hours time span. For these graphs, we regrouped the time in four hours.When women and men were reporting more than one activity we asked them to try to precise what was the main activity among all the ones reported. Thus, with “main activity” is intended the activity that women and men report as the most important during the respective time span. The other calculation was done based on time spending. Based on the diary, we calculated how many minutes were spent on average for the activities reported by women.

[22] MoLSAEO, “National Strategy on Gender Equality and Domestic Violence 2007-2010”, Tirana, December 2007

[23] According to MICS 2005 data there is a difference between the attendance rate in urban areas which is 48.2, compared with 34.7 percent in rural areas.

[24] UNCT, Common Country Assessment 2004, Tirana, 2005

[26] UNCT, Common Country Assessment 2004, Tirana, 2005

[27] Regarding this, reference may be made to the publication “Becoming an adult: challenges and potentials for youth in Albania”, (Danaj E., Festy P. et al, 2005) where it is concluded that the role of the family is central for the current Albanian society, being the safest place in front of a very chaotic and unregulated labour market, a suffering educational system and a very weak welfare state.

[28] Here we could bring the example of Italy, where one of the cases of CSOs work is the creation of care services for the elderly at home. This ensures the daily care at home from specialized nurses. (G. Moro, “Azione Civica” Carocci Faber, 2005)

[29]In 1918, 75% of unmarried males aged 30 and 55% of married males lived with at least one parent, despite the high mortality of relatively old-aged parents. (Danaj E., Festy P. et al, 2005)

[30] In this paragraph, we refer to national scale data, taken from various Censuses in Albania, in order to illustrate the general situation. Nevertheless, in this research, care for the elderly is not among the most important activities as we focus on urban areas and also there is a low number of extended households among the participating in the research.

[31] In the social insurance scheme it is included also the maternity leave with the following benefits: benefits for maternity, benefit for maternity in the case of changing of the job, payment for the newborn. The incomes for the maternity leave are paid to the new mother and only in the case she has completed 12 months in the social insurance scheme.

[32] Informal payments in outpatient care represent about 11% of the total expenditure, in contrast to hospital care, where they represent close to 25% of the total expenditure. Among people giving “gifts” during a hospital stay (60% of all cases), 43% said the gift was requested or expected. In the case of outpatient care, about 40% of the people who went to the public health centres said they were required or expected, while 25% of those who went to a nurse mentioned such requirements. (World Bank, Albania poverty assessment, June 2003 )

[33] For additional inormation on informal payment for health care services, refer to the World Bank report “Albania Poverty Assessment”, June 2003

[34] UNDP, “Gender Policy Analysis in the MoH”, 2006, Tirana

[35] USAID, “CEDAW Assessment Report, Albania” prepared by Chemonics International, December 2005

[37] This happens due to informality regarding the declaration of incomes. Salaries declared with social insurances are often much lower than the real ones and, therefore, calculation of maternity leave benefits is much lower.

[38] MoLSAEO, National Strategy on Gender Equality and Domestic Violence, December 2007, Tirana

[39] Regarding pregnant women, at present, if they are not insured they have to pay. This is a very recent question, because till now pregnant women making check ups at consultancy rooms were benefiting from free services, whether insured or not. The amount is not so high for a well paid woman in the capital, but it can be considered extremely high for women without incomes and economically dependent. Interviews with health care professionals in Librazhd, Paskuqan and Tirana, indicate that this could affect the already started decrease of the number of pregnant women making checkups.

[40] UNDP & SEDA, National Human Development Report, 2005, Tirana

[41] UNDP & SEDA, National Human Development Report, 2005, Tirana

[42] These figures refer to INSTAT (www.instat.gov.al). The real figures for unemployment are higher because a great number of unemployed do not register to the Labor offices thus they are not counted in this rate. According to LSMS 2002, around 45% of the unemployed are not registered and counted.

[43] CEDAW Committee: 34. The Committee is concerned about the higher unemployment rate among women than among men. The Committee is concerned that women are not able to receive adequate training and retraining to compete in the job market. The Committee is concerned about discrimination in hiring women, especially in the emerging private sector (USAID, “CEDAW Assessment Report, Albania” prepared by Chemonics International, December 2005)

[44] With regard to this situation, MoLSAEO has undertaken some legal and sub-legal initiatives, such as the law “On the encouragement of employment,” CoM Decision no. 632, dated 18.09.2003 “On the encouragement of employment of unemployed women jobseekers,” etc., which seek women and girls’ employment. A total of 3 programs for the encouragement of employment favoring women and girls have been implemented; in 2004, implementation of the CoM Decision no. 632, dated 18.9.2003 “On the program of encouragement of employment of unemployed women jobseekers” and Order no. 394, dated 23. 02. 2004 “On tariffs in the vocational training system” of the Minister of the MoLSA, began; according to Order 394, dated 23. 02. 2004 “On tariffs in the vocational training system,” public vocational training centers should register persons from groups in need free of charge; the network of non-public (private and NPO’s) vocational training courses for women and girls has expanded. In 2004, a total of 93 vocational training courses were licensed and of these 75 are mainly for vocations for women and girls. These courses spread throughout the country; NPOs have opened employment centers for women and girls, such as in Tiranë, Elbasan, Berat (MoLSA, Strategy for Social Service, Tirana, 2005) te lutem kontrolloje??

[45] Danaj, E., (2003). Mother's employment and children poverty: Analytical report, 2003, INSTAT, Tirana.

[46]Based on the interview with Monika Kocaqi (key informer), Executive Director of the “Refleksione” Association, August 30, 2005, cited in the UNIFEM & GADC report “Creating economic opportunities: a strategy for preventing trafficking”, 2006

Supported by the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) under the auspices of its sub-regional Programme “Gender-Responsive Budgeting in South East Europe: Advancing Gender Equality and Democratic Governance through Increased Transparency and Accountability” . The Programme is implemented with funding from the Austrian Development Cooperation and Cooperation with Eastern Europe, and the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland.

Supported by the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) under the auspices of its sub-regional Programme “Gender-Responsive Budgeting in South East Europe: Advancing Gender Equality and Democratic Governance through Increased Transparency and Accountability” . The Programme is implemented with funding from the Austrian Development Cooperation and Cooperation with Eastern Europe, and the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland.